When health warnings first appeared on packets in 1971 and the rules for cigarette advertising rules were changed, tobacco companies were faced with the challenge of maintaining brand awareness and driving sales in a market made more aware of the risks than ever before.

The change in rules, coupled with a fresh approach to advertising in general, gave birth to a unique genre of advertising that neatly ticked the boxes of the rule book yet created an art form. As with Surrealist art, these ads aimed to surprise and intrigue the viewer by replacing the objects people expected to see in a particular scene with something incongruous – in this case, a packet of cigarettes.

Collett Dickenson Pearce was tasked with the advertising for Benson & Hedges in 1973. CDP, lead by the indefatigable John Pearce (who famously once fired Ford, then CDP’s biggest account, because the car-maker kept trying to change the ads) was also the place where many now famous people would cut their teeth on campaigns for Hovis Bread, Cinzano and Birds Eye. Lord David Puttnam, Sir Alan Parker, John Hegarty, Charles Saatchi, and Sir Ridley Scott to name a few.

The story goes that Frank Lowe, Managing Director at CDP in 1977, had two finished campaigns to present. After much debate, he took both campaigns to CDP’s Creative Director, Colin Millward, and asked him his view.

Colin said, “…one will let you sleep at night, the other will make you famous.” Thankfully, both CDP and B&H decided not to sleep at night. The rest is history.

Art director Nigel Rose and his team at CDP (including John Emperor who designed the packet logo, and Alan Waldie) were tasked with creating a campaign which turned the familiar golden packet into an iconic emblem, with ads that played with their audience and challenged the mind, whilst neatly positioning the brand to represent culture, sophistication and cool. No people were allowed to be shown so an abstract style evolved without a word of copy, except for the obligatory health warnings.

My previous post on Brian Duffy showed some of his work for B&H, other photographers’ work included greats like Graham Ford, Max Forsythe, Rolph Gobbits and the late Jimmy Wormser.

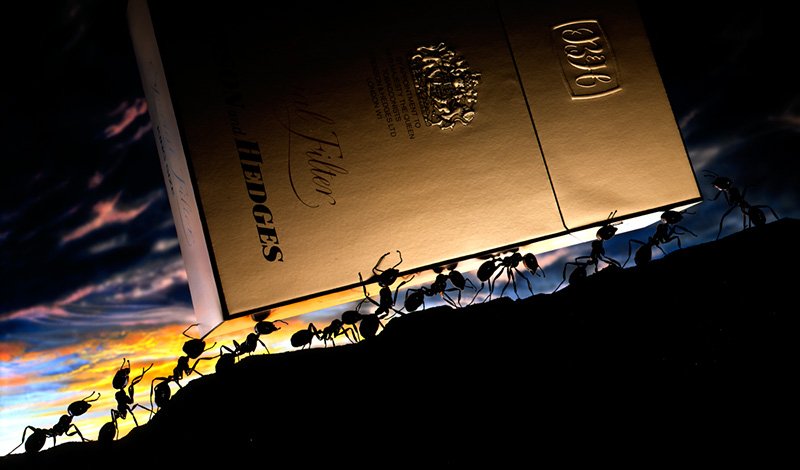

Ants 1986 Nigel Rose (AD) Graham Ford (photographer) Terry Kemble (model maker)

Magnet 1986 Rob Morris (AD) Graham Ford (photographer) Terry Kemble (model maker)

Goldfish 1985 Nigel Rose (AD) Graham Ford (photographer) Terry Kemble (model maker)

Graham Ford: “I was into point-source lighting at the time and tracked down the smallest most powerful tungsten lamp I could find — a 1.5cm square reflecting 500W projector bulb, the most efficient point source that I ever found, and I used it often afterwards. It gave a light very similar to sunlight when used at the correct distance and was powerful enough to give a reasonably short exposure, between 30–90 seconds at around f45 on 10×8 film.

We did a basic setup which looked promising, but the cat was very crude and unconvincing. The agency art buyer found a brilliant animal illustrator who came to the studio and made a beautiful cardboard cutout. We softened the edges slightly with bits of fur and plastic pondweed.

I thought we should give the picture a sense of time and place and chose beautiful Basildon on a sunny morning. Hence the diamond patterned windows, net curtains, Artex-style wallpaper, kidney-shaped glass dressing table on nylon. It went very well with the goldfish bowl. The hard light, strong shadows, and refracted light looked wonderful — the cat came to life.’

The photography of this shot was fairly straightforward. We blurred the curtain to separate it from the cat shadow using lines of very fine wire attached to different parts of the curtain so we could control the movement accurately. I had an armory of techniques which I would add to each time a problem had to be solved. I used multiple exposures often, this was not a problem with the film, you could keep adding different parts of the image on to the one sheet of film. Exposures were sometimes ten minutes long with twenty or more flashes, bits of black velvet being shoved in and out, lights being moved around.

It was less usual in those days for the client to reject or demand changes. To do so would be expensive too, as changes would require a re-shoot. Retouching was a very specialised business before computers, and there were few who could do it well. It was often used in a minor way, or to achieve effects that could not be done in camera, but my aim was always to do everything in camera if possible.”

[interview with Graham Ford by kind courtesy of Ken Sparkes click here to see full page]

Chameleon 1986 Nigel Rose (AD) Max Forsythe (photographer) Terry Kemble (Modelmaker)

Max Forsythe: “The finished shot looks very much like the original layout, but the struggle was how to light it. No conventional lighting seemed suitable.

After about 2 days of messing about, I finally settled on sunlight coming through the studio window with a bit of BBQ grill to cast the shadows.

The Chameleon and the pack were both models, we did get a real one in the studio but soon realised that it was not possible to work with it (it kept disappearing). They were about 5 times real size which made it possible to shoot on 10×8.”

Escapologist 1980 Nigel Rose (AD) Jimmy Wormser (Photographer)

Pyramids 1978 Neil Godfrey (AD) Jimmy Wormser (Photographer)

Swimming pool 1978 Alan Waldie (art director) Jimmy Wormser (photographer)

Inspirational stuff especially when you bear in mind that these shots were created entirely in-camera long before Photoshop was a twinkle in Adobe’s eye!

With the current laws on tobacco advertising (ie. it’s banned) it’s unlikely we’ll ever see a repeat of these ads. As a student, these ads took pride of place on the walls at college and continue to inspire me with their composition and beautiful lighting. No wonder it’s often referred to as ‘the golden era’ of advertising. We’ve definitely lost an art form and (without getting into a debate about smoking) I’d love the opportunity to be involved in a campaign which takes the product as an art form and turns convention on its head.

With huge thanks to Julian Gratton at RedC, Ken Sparkes, Graham Ford, Jimmy Wormser, CDP, Benson & Hedges, Max Forsythe, Wikipedia and Advertising Archives.