As Brian Levant’s mother, brother and sister were waiting to give him a ride home from the skating rink one day, the neighbours’ nanny appeared, pushed a camera through the open window and took a picture. Residents of the Chicago suburb of Highland Park were used to the nanny doing that, along with her French accent, her penchant for wearing men’s coats and boots, and the look and gait that led children to call her “bird lady.”

But her photograph of Carole Pohn and her children from 1962 is one of the very few prints the nanny ever shared; she gave it to Pohn, a painter, telling her she was “the only civilized person in Highland Park.” Pohn says she tacked the print up on a bulletin board “with a million other things”—an act that embarrasses her today. After all, she says, the nanny is “a photographer of consequence now.”

The nanny’s name was Vivian Maier. Wearing a twin-lens Rolleiflex around her neck, more body part than accessory, she’d snap pictures of anything or anyone as she lugged her charges on field trips into Chicago, photographing the elderly, the homeless, and the ‘forgotten’. The photographs reveal teeming streets, children at play in an alley, couples captured in a sleepy embrace, the intricate latticework of an elevated train platform, a drunk smeared in filth.

And for years, they were probably seen by no-one but the solitary Chicago nanny and amateur photographer who shot them.

Maier’s recent, sudden ascent from reclusive eccentric to esteemed photographer is one of the more remarkable stories in American photography. Though some of the children she helped raise supported Maier after they came of age, she couldn’t make the payments on a storage locker she rented. In 2007, the locker’s contents ended up at a Chicago auction house, where a young real estate agent named John Maloof, working on a book about his NW side neighborhood and looking for photographs, came across a box of negatives. Maloof, an amateur historian, spotted a few shots of Chicago he liked. He bought the box of 30,000 negatives for $400. Although he wasn’t an art historian as such, Maloof felt compelled to buy more of the work and, having found other buyers of the work from the same auction, bought whatever he could from them too. Since then, Maloof has amassed an archive of Maier’s life and work. Stashed in the attic studio of his Portage Park home are her cameras, 2,000 rolls of film, 3,000 prints and 100,000 negatives, as well as many 8mm movies and audiotapes. Stacks of old suitcases, a steamer trunk of clothes and scrapbooks filled with newspaper clippings are stacked against one wall.

Maloof knew the locker had belonged to someone named Vivian Maier but had no idea who she was. He was still sifting through the negatives in April of 2009 when he found an envelope with her name penciled on it. He Googled it and found a paid death notice that had appeared in the Chicago Tribune just a few days before. It began: “Vivian Maier, proud native of France and Chicago resident for the last 50 years, died peacefully on Monday.” In fact, Maloof would later learn, Maier had been born in New York City in 1926, to a French mother and an errant Austrian father; she had spent part of her youth in France (where she met a photographer friend of her mothers) but she worked as a nanny in the United States for half a century. The children she looked after described her as a Mary Poppins-like figure who took them on wild adventures and showed them unusual things. She managed to travel extensively and ended back in Chicago, winding down her career in the 1990s. She worked for one family in Chicago for 17 years and as they tell it, she neither made nor received a single telephone call the entire time.

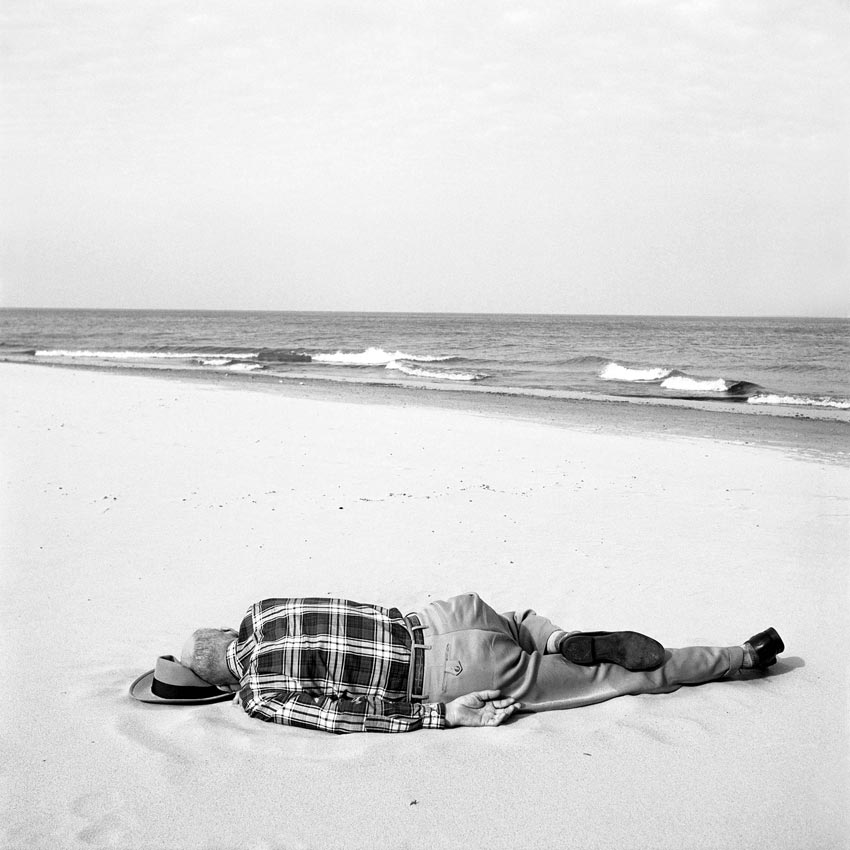

On her days off, she would walk the streets taking photographs, poignant and humorous scenes from everyday life. A man sleeping on the beach, children smiling, a woman dressed in her finest climbing into a ’57 Chevy.

In late 2008, she slipped on a patch of ice, sustaining a head injury that spiraled into other health problems. She died April 20, 2009, age 83.

Maloof started a blog and began posting Maier’s photographs on Flickr. Soon, people who knew more than he did about photography were telling him he had something special on his hands. News reports followed, then interest from galleries. There now have been Vivian Maier shows in Chicago, New York and Los Angeles, as well as Germany, Norway, England and Denmark. Maloof has edited a book of her work, Vivian Maier: Street Photographer, which was published in November, and has raised money for a documentary film about her that is in progress.

Maloof has now accumulated at least 100,000 Maier negatives, buying them from other people who had acquired them at the 2007 auction; a collector named Jeffrey Goldstein owns an additional 15,000. Both men are archiving their collections, posting favourite works online as they progress, building a case for Vivian Maier as a street photographer in the same league as Robert Frank—though Goldstein acknowledges that gallery owners, collectors and scholars will be the ultimate arbiters. A photography collector, Ron Slattery, a collector of photography and owner of BigHappyFunhouse was at the original auction and claims to have saved her negatives from landfill as the auction house was throwing negatives away.

Current professional opinion is mixed. Steven Kasher, a New York gallerist planning a Maier exhibition this winter, says she has the skill “of an inborn melodist.” John Bennette, who curated a Maier exhibition on view at the Hearst Gallery in New York City, is more guarded. “She could be the new discovery,” he says, but “there’s no one iconic image at the moment.” Howard Greenberg from the New York Gallery says, “I’m taken by the idea of a woman who as a photographer was completely in self-imposed exile from the photography world. Yet she made thousands and thousands of photographs obsessively, and created a very interesting body of work.”

What made Vivian Maier take so many pictures? People remember her as stern, serious and eccentric, with few friends, and yet a tender, quirky humanity illuminates the work: old folks napping on a train; the wind ruffling a plump woman’s skirt; a child’s hand on a rain-streaked window. “It seems to me there was something disjointed with Vivian Maier and the world around her,” Goldstein says. “Shooting almost tethered her to people and places.”

Her street photography images remind me of Cartier Bresson and Helmut Newton, Elliot Erwitt and Walker Evans but they have an innocence about them, a lack of pretense and a sense of joy that being in love with photography and the ability to capture life in an instant can hold. Maier shot a huge amount of images (John Maloof still has 100’s of boxes of exposed film left to process) especially self portraits which are really stunning and intriguing, not only because we know a little about who she was now but also because they themselves tell us about the kind of person she was. She never smiles – the expression is always the same; slightly startled and always reflected in a mirror or window.

For me, the composition of her work is beautiful – yes I love the square format and B&W images of the 50’s and 60’s, but the balance and framing is quite stunning.

Personally, I struggle with the idea of a few people potentially making a huge amount of money from this. Yes it’s legal (Maier had no estate or relations to pass copyright onto apparently) and yes, they would have ended up probably as landfill if they hadn’t had been bought at the auction so I guess I should be thankful, but it is altruistic nonetheless and I’m still slightly uncomfortable to have to credit the copyright in the images used in this post to the John Maloof Collection and Jeffrey Goldstein.

But thanks John – keep up the great work and I look forward to seeing the exhibition sometime soon. And yes, I promise to buy the book!

Malcolm

Images by kind courtesy of The John Maloof Collection

see also Jeffrey Goldstein www.vivianmaierprints.com