Marlboro is far and away the world’s best-known and biggest-selling cigarette, with a huge global presence and total sales now still well in excess of $20bn. Ownership is split primarily between what are now two entirely separate companies: Philip Morris USA and Philip Morris International. Ironically, as the tobacco industry comes under ever more intense regulatory pressure, Marlboro is still going from strength to strength at least in terms of market share. In its home territory, more than four out of every ten cigarettes smoked is a Marlboro, the brand’s highest-ever level of market share. That dominance is mirrored to a lesser extent in just about every other territory the brand is marketed, as other cigarettes see brand share erode in favour of Big Red. The reason? Leo Burnett’s Marlboro Man and the abiding power of marketing, even in an industry where advertising itself is virtually forbidden.

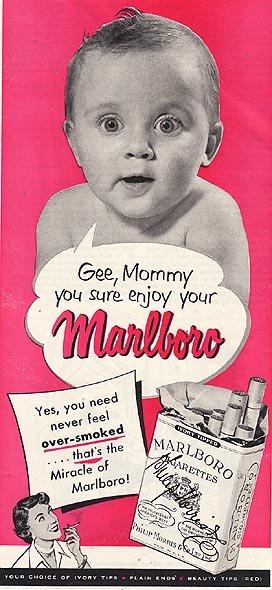

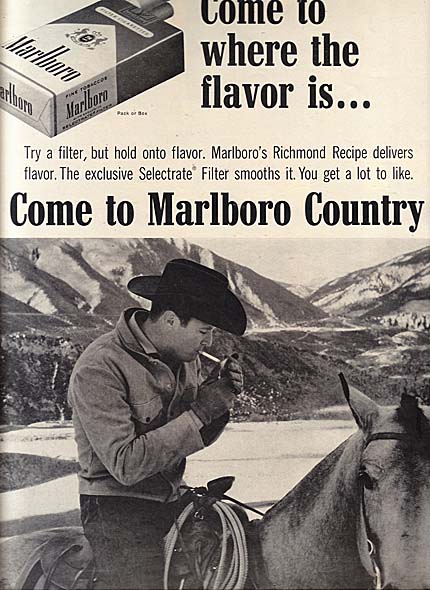

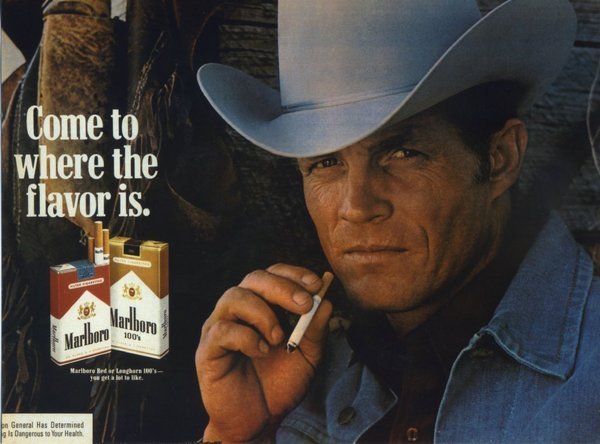

In the 1950’s there began a suspicion that smoking cigarettes may be linked to lung disease. Filters were generally decided to be the answer but Real Men, which was where the sales dollars were, didn’t smoke a filter cigarette. The question then became how to make this cigarette appeal to men? The Leo Burnett advertising agency in Chicago was consulted and came up with campaigns that showed Real Men smoking filtered Marlboro cigarettes. First came the series with men with a tattoo on their smoking hand, tattoos were masculine then. Next came the long-running cowboy series, all in an attempt to convince the public that men could demand a filter too. It worked and the Marlboro Man became as famous as other Leo Burnett creations like Pillsbury Dough Boy and the Jolly Green Giant.

Louis B Cheskin, whose original specialism was the psychological use of colour, proposed that the Marlboro packaging should suggest a medal worn around the neck as an unconscious cue of masculinity. He supported the cowboy campaign and later had a hand in Marlboro’s introduction of the hard, flip-top cigarette packet – an invention that, by creating a ritual around opening a pack, contributed almost as much to the addictive nature of cigarettes as nicotine.

James Twitchell, author of 20 Ads that Shook the World, said the Marlboro Man was an achievement because it found success at a time when Americans were learning that cigarettes were genuinely dangerous, addictive products that could kill you.

“The Marlboro Man was strong, powerful. He never speaks. He’s so tough. The genius of the ad is that at the same time there was a rising realisation that this thing will kill you, it was identified with a character who was, on the face of it, indomitable.”

Sadly, the three actors who played the Marlboro Man died of lung cancer. One sued Phillip Morris and the cigarettes became known colloquially as “cowboy killers”.

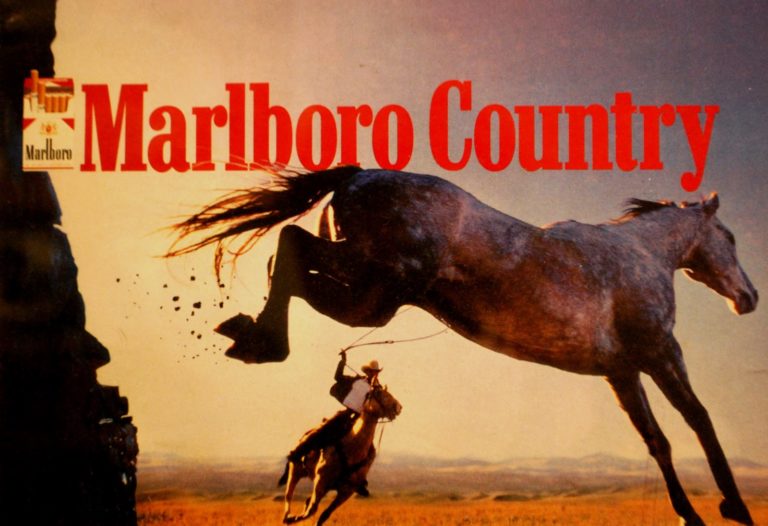

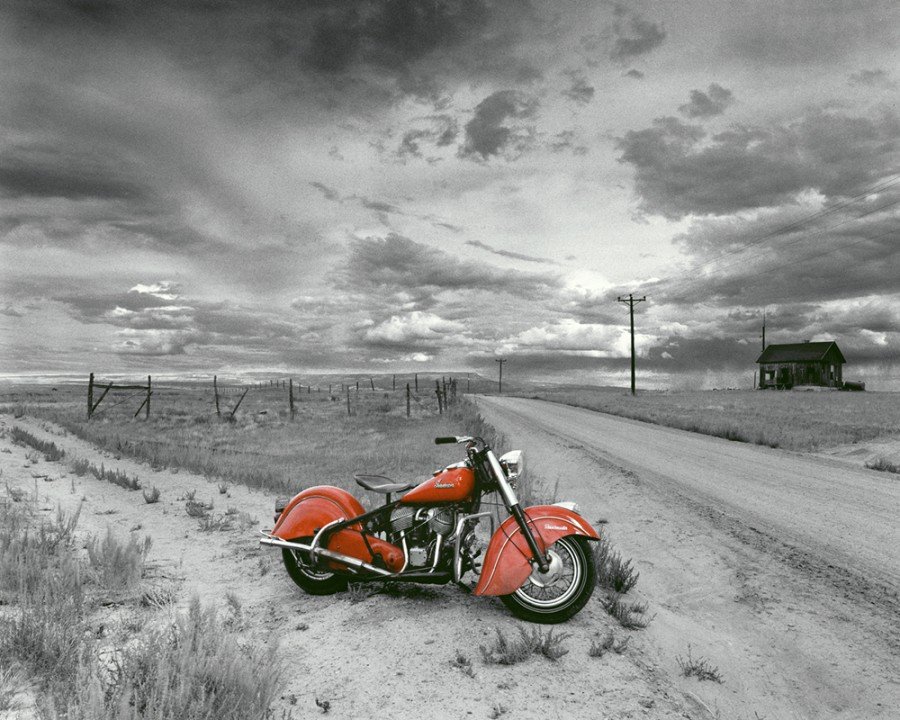

Richard Prince was commissioned to shoot the iconic images, shooting with Ektacolor film

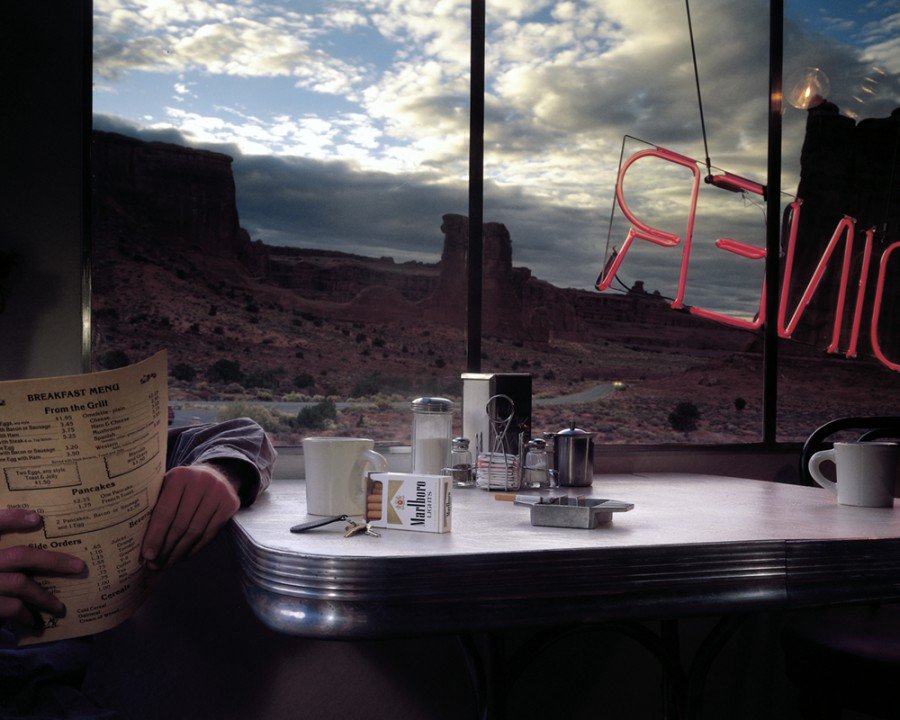

Associating Marlboro with the rough, tough and masculine life of a cowboy worked well – still does, although the references to cowboys were replaced in the 80’s by a more sophisticated campaign which retained the suggestions of the wild western lifestyle but catered for a more educated audience, especially in Europe where the cowboy references were seen as irrelevant. As smoking bans in cinemas (1987)and advertising & brand restrictions on screen started to take effect, an audience that had been introduced to the slightly heady and surreal world of Star Wars V, the slightly camp but awesome Top Gun, the clean living style of Superman and ET were responding to the B&H advertising (see previous post) hence Leo Burnett were tasked with introducing in new approach to promote the Marlboro brand which also ticked the boxes/neatly sidestepped the new guidelines on cigarette advertising.

Among the photographers commissioned to shoot the new ads was Peter Lavery – a brilliant photographer who I spent 4 amazing weeks with during my stint of work experience at college in the 80’s (I think I learned more in that 4 weeks than the whole 3 years!) whose passion and energy still inspire me today.

He was given a fairly open brief to travel the wild west with art director Gordon Smith, armed with his trusty Gandolfi under one arm and a few boxes of 10×8 under the other. In 1993 he produced the shot of the motorbike which really defined the new style.

While it’s good to look to the past, it’s also intriguing to look to the future. But is there a future for cigarette advertising in the UK?

Well for tobacco cigarettes the answer looks like a resounding no, and in fact cigarette companies may soon lose even more of their ability to build their brand.

Back in December 2015, Australia became the first country to introduce plain packaging laws for cigarettes and pretty much the rest of the world has followed. As a result of a lengthy consultation on the topic, the UK will soon introduce plain packaging for cigarettes and the new ruling is due to be announced during the Queen’s speech in May. This will mean that all cigarette packets will look exactly the same as each other – typically an unattractive colour with several warnings about their damage to health.

So from the glamour of Hollywood endorsements and Formula 1 cars, cigarettes will soon lose their last touch of personality and become uniform, ugly boxes.

As for whether smoking will ever be entirely outlawed, the verdict is a little more uncertain. For the moment everything seems to be pushing towards making smoking unpopular, rather than making it illegal which runs the risk that it will go underground.

In such a scenario the government would lose any tax they gain from the sales of tobacco (around £12.1 billion in 2011/2012), while still footing the bill for subsequent healthcare (estimated to be around £5 billion in 2005/2006). With around 20% of the adult population still smoking, this could prove very costly.

However, if the stricter measures cause the number of smokers to dwindle to a select few, it’s definitely possible that smoking will one day be banned for good.

Thanks to Peter Lavery, Leo Burnett, Campaign, DrFox, BBC & Wikipedia