David Bailey is an inspiration to many photographers including myself – not so much his technique or work but the way he works and the passion he has for photography. I might have that wrong, to be honest – he’s more a lover of art than photography itself and sees his work as an art form. Who am I to argue..?!

From Vogue magazine fashion photographer to filmmaker, painter, and sculptor, David Bailey is a cultural icon who has been at the cutting edge of contemporary art for 50 years. A working-class Londoner, he befriended the stars, married his muses and still captures the spirit and elegance of his times with his refreshingly simple approach and razor-sharp eye.

During the mid-’60s, no one personified swinging London more than fashion and celebrity photographer David Bailey, whose iconic images of everyone from The Beatles to Julie Christie were seen around the globe.

Growing up in war-torn London, David Bailey was heavily influenced by films. “In the winter“, he recalled, the family “would take bread-and-jam sandwiches and go to the cinema every night because in those days it was cheaper to go to the cinema than to put on the gas fire. I’ll bet I saw seven or eight movies a week. The only cultural input was Hollywood. My whole cultural influence is really Hollywood—old Hollywood, ’40s Hollywood. We’d go to the cinema seven times a week; it was cheaper than staying home because you didn’t have to put money into the gas machine that kept the fires going in the house. I think when I was around 12 my heroes were Fred Astaire, John Huston, and an ornithologist named James Fisher. I thought Fred Astaire was the most glamorous thing in the world. And I thought John Huston was like a white hunter.”

Dyslexia and suffering from dyspraxia, Bailey was told at school that he was stupid and it seems that Britain’s greatest photographer wanted to prove he was brilliant at something.

“Being dyslexic, I was told that I was an idiot all the time, but I knew I was smarter than the teacher so I was sort of arrogant. When you’re dyslexic it pushes you into doing things like painting and photography. Or bird-watching: At one point I wanted to be an ornithologist.”

In one school year, he claims he only attended 33 times. He left school on his fifteenth birthday, to become a copy boy at the Fleet Street offices of the Yorkshire Post.

“I had sort of discovered chemistry and photography when I was 10 or 11. I had my mother’s Brownie and I used to process the film down in the cellar. So I had an early interest in photography. But it was mainly a technical thing: I loved mixing up chemicals. Then I used to paint and draw. That’s the only thing I was ever top in at school. I had lots of jobs—you know, a kind of John Steinbeck syndrome. I was a carpet salesman, a shoe salesman, a window-dresser, a copyboy for the Yorkshire Post, a runner for 20th Century Fox. And when I was 17 I was a bad-debt collector. That was tough.”

Called up for National Service in 1956 then serving with the Royal Air Force in Singapore in 1957, the appropriation of his trumpet forced him to consider other creative outlets, and he bought a Rolleiflex camera. A keen artist influenced heavily by the work of Picasso, Bailey found a way of articulating through the medium of photography and became brilliant at it. While in the RAF, he developed his interest in photography and taught himself to read.

“I was a parachutist, believe it or not. I volunteered for jungle rescue because then I got excused… didn’t have to do anything. I could just sit in my hut on the runway and paint and read. I read about five books a week. I read everything—Tolstoy, Dostoevsky,… all of the Russians.”

|

| Self-portrait with Picasso pin-up at his billet, Singapore, 1957 |

“I always painted because it was the only thing I could do. I saw some paintings by Picasso of Dora Maar and it was like getting religion. Suddenly my whole vision changed. What Picasso showed me in an instant was there are no rules. Discovering Picasso opened up a whole network of things. Then I played trumpet—rather badly—because I wanted to be Chet Baker, and I saw these wonderful record covers of Baker and all these West Coast jazz musicians that were done by William Claxton. And that re-sparked my interest in photography. But the picture that probably inspired me the most was that famous Cartier-Bresson photograph, “Kashmir, 1948, Muslim Woman Praying at Dawn in Srinagar.” So when I was 16 I started mucking around with cameras more seriously. Then I was caught by the British government, and they put me in the Air Force. I went to Singapore for two years—’56 to ’58. I still played the trumpet, but I lent my trumpet to an officer and a gentleman who never gave it back. As a private, I had no comeback. But Singapore was a tax-free port and when you bought a packet of cigarettes they’d throw in a camera practically for free. So I got a camera.“

He was demobbed in August 1958 and determined to pursue a career in photography, he bought a Canon rangefinder camera. Unable to obtain a place at the London College of Printing because of his school record, he became a second assistant to David Collins, in Charlotte Mews. He earned £3 10s (£3.50) a week and acted as studio dogsbody.

“Then I wrote to every photographer in London I thought wasn’t bad, and it happened that the two most famous ones of that period both replied, both offered me a job. One was John French; the other one was Tony Armstrong-Jones [Lord Snowdon]. Snowdon gave me tea from a silver teapot and said, “Are you any good at building room sets because I do a lot of room sets?” And I thought, “I don’t like the sound of this,” so I said, “No, I want to be a photographer, not a carpenter.” Anyway, John French gave me a job as a third assistant. I was only there 11 months, but I worked up to the first assistant.”

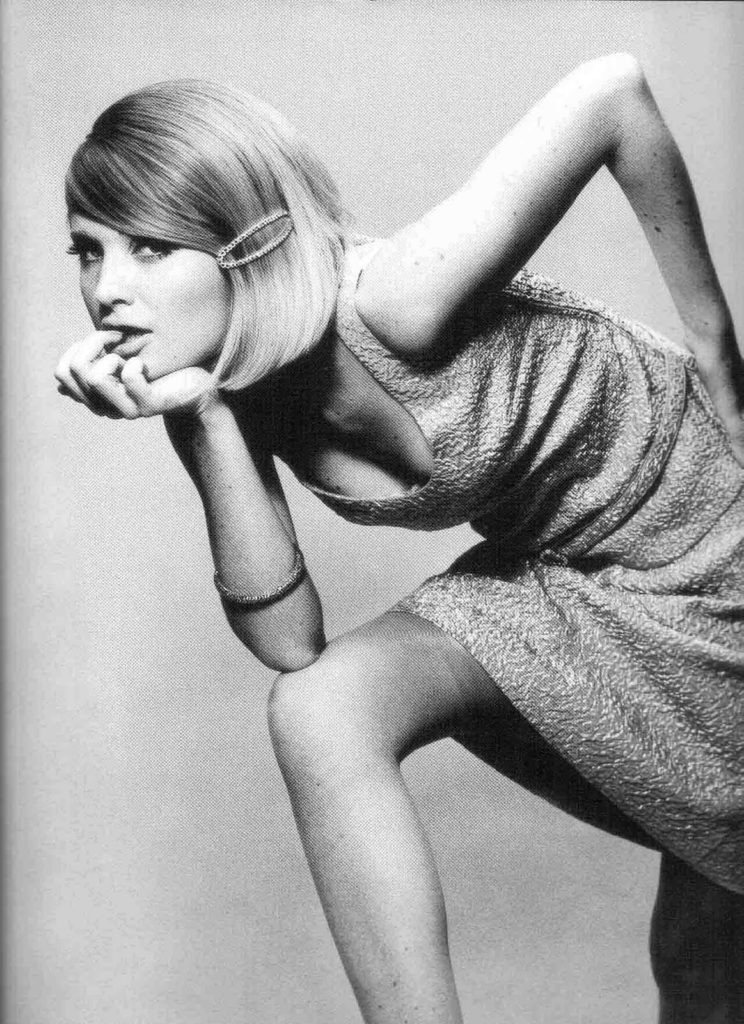

In 1959 John French (who he formed an unlikely bond with) helped him get a job at The Daily Express, then worked as a photographer at John Cole’s Studio Five before being contracted to his first commission from Vogue with art director John Parsons. His working-class background (of which he’s extremely proud) defined him as an outsider, however, French and Parsons were both homosexual and identified with the outsider in Bailey. Bailey’s ascent at Vogue was meteoric. Within months he was shooting covers and at the height of his productivity, he shot 800 pages of Vogue editorial in one year. Penelope Tree, a former girlfriend, described him as “the king lion on the Savannah: incredibly attractive, with a dangerous vibe. He was the electricity, the brightest, most powerful, most talented, most energetic force at the magazine”.

Vogue was looking to attract a younger audience and saw the energy and potential in a foul-mouthed young photographer from East Ham. The world of fashion was changing – the foppish elite, typified by Cecil Beaton, who required no further grooming in etiquette to know which spoon to use at breakfast with the Royals was about to be toppled by Bailey, Duffy, and Donovan, aka The Black Trinity. His “take me as I am” attitude came fully formed: he insisted on shooting Jean Shrimpton, even though Vogue didn’t want her. Vogue’s Sheila Wetton once said “I worked in fashion for 57 years and in all those years I only cried twice: both times because of David Bailey.’”

“The only way to be creative for me in the ’60s was in fashion photography – in an instant, I knew there were no rules – that’s the lesson I learned from Picasso.” David Bailey

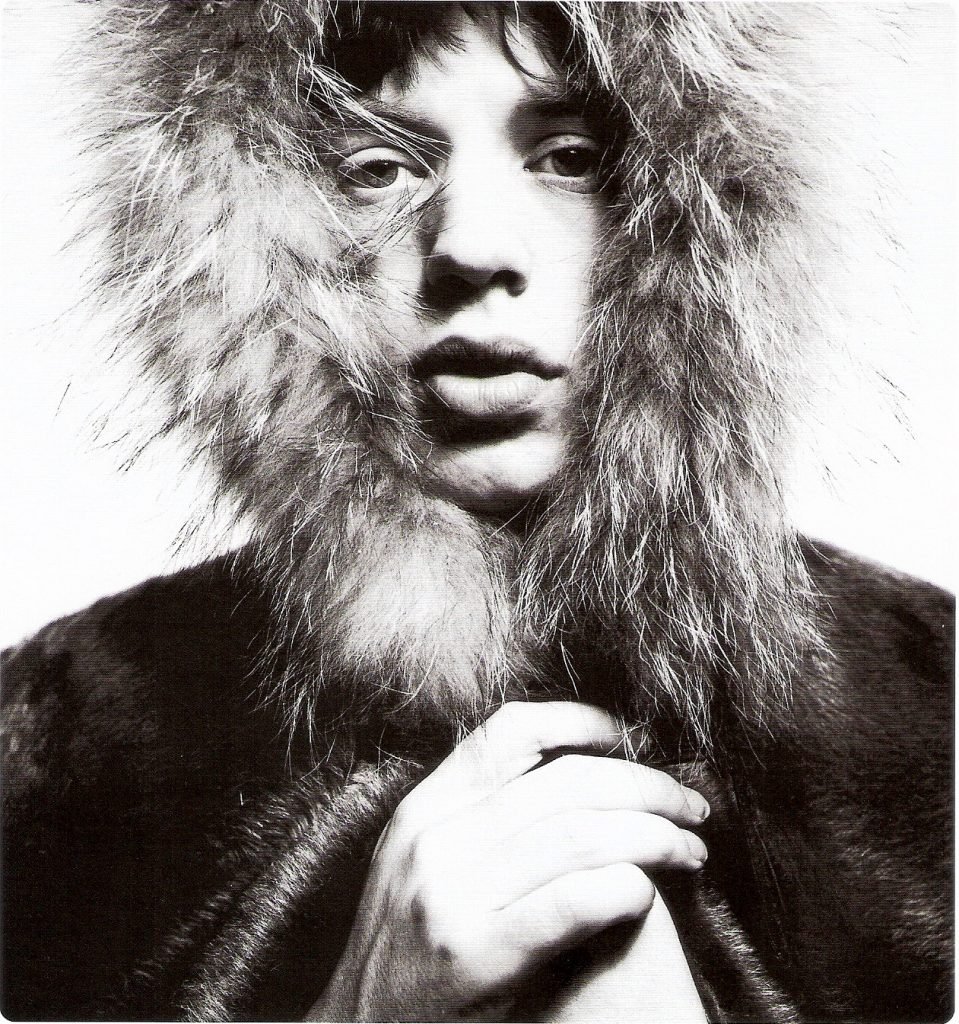

Well before he had released his pictures of Jean Shrimpton, his girlfriend for the first half of the 1960s, and stars such as Mick Jagger and PJ Proby (who appears in a crucifixion pose in the 1964 poster collection Box of Pin-Ups), David Bailey had transcended the photographer’s role as mere observer and taken centre stage. More than three decades after he starred in his first Olympus camera ad (where someone asks: “Who does he think he is – David Bailey?”) he remains the best-known British photographer, despite the stunning work of younger talents such as portrait photographer Nigel Parry.

“Looking back, I think they’re pretty good pictures. They look better now than they did when – I was groping around trying to find a way to go then. I just photograph what I can see. I don’t consider I take pictures, I take pictures.”

“The photographer that is closest to me is a French photographer, Nadar from 1860’s – I know what he knew. As soon as people come through the door I’m photographing them. I watch the way they move and shoot their space. That’s why I like my pictures – you can’t copy what I do because I don’t do anything. I just do it with dialogue by talking to people. I’m not really looking for anything I’m looking for that person, I’m looking for what they have. I want them to look like they have no limitations. I want to capture their personality. I don’t want anything else from them. It’s the accident that’s exciting.”

“Women love him” in the words of Jean Shrimpton, who now runs a hotel in Cornwall. “Gays adore him. Children and animals run to him. Mothers dote on him. He is universally attractive, except to fathers.” Now that he has three children of his own with his fourth wife, the model Catherine Dyer, he seems to have softened somewhat in his behavior towards straight men.

Abbey Lee | Bailey 2010 for ID Magazine

Catherine Dyer – “he has a way of seeming flippant but one thing he’s not a joker he takes what he does very seriously. That’s part of it. And the dedication – he’s working at it all the time; he’s never satisfied. It’s always a disappointment. So he just wants to do better. His disappointment doesn’t make him give up, it makes him do more.” Persistence is the key to why he still works and is the oldest photographer to still be shooting for Vogue.

Box of pin ups

The “Swinging London” scene was aptly reflected in his Box of Pin-Ups (1964): a clever form of marketing, the box of poster-prints of 1960s celebrities including Terence Stamp, The Beatles, Mick Jagger, Jean Shrimpton, PJ Proby, Cecil Beaton, Rudolf Nureyev, Andy Warhol and notorious East End gangsters the Kray twins

Andy Warhol from Bailey’s ‘box of pin-ups’ 1964

Bailey is still fond of film (Kodak Tri-X is his favourite) and believes that digital cameras and photoshop have taken away the personalities of photographers and photography. I have some sympathy with that and personally feel that the creative process has lost the opportunity for a ‘happy accident’ and I seem to be spending more time infront of a computer than behind a camera!

“Usually for portraits, especially men, I shoot on 10×8. There’s no set thing it just depends on the situation. If I do a location shoot like I’m in India in a couple of weeks, we’ll take digitally because of the X-rays. It’s expensive to take a picture on 10×8, every click costs about £50. Actually more I think and Vogue gets annoyed. Well, they all get annoyed asking why I can’t use digital.

In the end, I don’t think digital is any cheaper, the time spent fiddling about with it and choosing it and printing it. These things take longer. On 10×8 I’ve never taken more than eight pictures, sometimes six. We used to shoot on 11×14, then I’d only take two, one on either side. Then it’s easier to choose because ones out of focus or one, someone’s blinked on. With digital, you spend hours in front of a television screen. But I think for the general market (digital) is fantastic, everyone can be a photographer.

The same thing happened in 1890 when they brought out the Box Brownie everyone said photography was finished, but it’s not, it just makes it harder because now everyone takes the same picture. The problem with digital for me is that there’s no accident. You can’t make an accident, like Rankin he takes a picture then looks at the screen. He moves it over a bit then does another. For me, there’s no magic in that. I mean I don’t know what’s going to come back, it’s kind of if I make mistakes it’s part of the creation in a way because the only way you can get creative is by making mistakes. With digital there are no mistakes, everything’s perfect.

You look at those photographic magazines and they’ve hundreds of fantastic, boring landscapes all the same. They do up the colour and it’s a picture of another tree. How many trees can there be that haven’t been photographed?”

Bailey has also worked as a director of TV commercials & documentaries and flirted with film direction too, working with Ridley Scott His works include ‘Beaton’, ‘Warhol’ (where he is filmed in bed with Andy Warhol) and ‘Visconti’.

His book Goodbye Baby and Amen is the complete record of his work and captures the decade he first flourished in, with portraits of the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, as well as actresses, politicians, artists, and writers of the day.

David Bailey, Archive One 1957-1969, published in 1999, includes the bulk of his early fashion and portraiture work but also unearths some photojournalistic gems taken in the early Sixties, most of London’s East End. Today, Bailey’s still going strong and shows no signs of slowing down. His most recent work includes portraits and celebrity shoots for Harper’s Bazaar, Italian Vogue, The London Times and Talk magazine, among other publications.

He’s also slightly obsessed by death – his most recent photographs and paintings feature death prominently with images of skulls and bones, dying flowers and he says “…my only problem is the race against death. I’ve got the fucking reaper on my back all the time“.

“Bailey’s reputation more than precedes him, it barges ahead, grabs you by the hand and asks you when was the last time you had a shag. Both physically and vocally he’s a barking presence in any room, not least when he’s working at his studio. Dressed more often than not in a dusty, unbuttoned flannel shirt thrown together with a pair of old baggy blue jeans, Bailey will flatter, flirt, disregard, insult, eye-up or even dance with a subject in order to get the picture he wants. It’s a disarming, if not bewildering, force.” Jonathan Heaf/GQ magazine

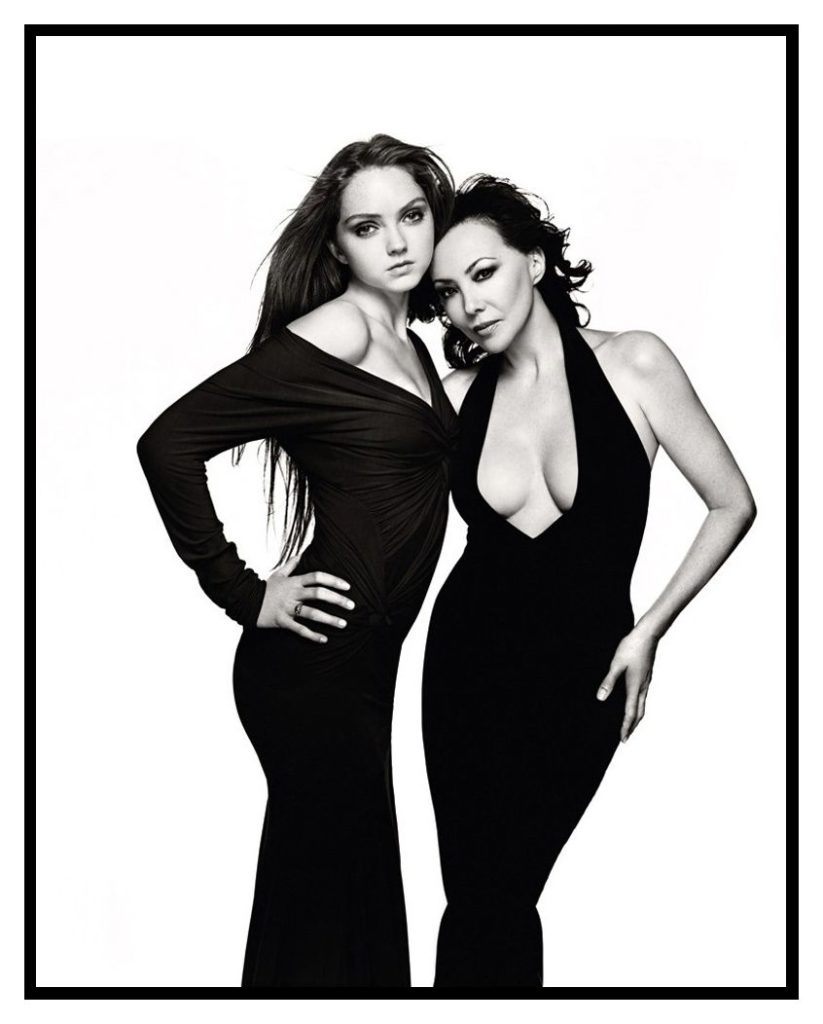

Marie Helvin & Lily Cole by Bailey

Approaching his 75th year, Bailey is showing no sign of slowing up. In his London studio and his country home in Devon, he continues to inspire and create one of the most varied and pertinent collections of any modern artist.

Four beats to the bar and no cheating (2010)

Featuring interviews with art critic Martin Harrison, former wife Catherine Deneuve, current wife Catherine Dyer and close friend Jerry Hall, this is a portrait of a private man who bared the soul of the swinging sixties and seventies with his photographs and films. Grounded, honest, open and ferociously creative, Bailey makes art the way Count Basie once described jazz when asked to define it: “Four beats to the bar and no cheating” In his photographs, this approach leads to the transparent style for which he has become famous. If possible, we can even forget we are looking at a photo, let alone a beautiful, exceptionally composed or creatively arranged photo. All we see is the person Bailey has photographed, in all his or her nakedness. Bailey’s admirers also give their views, including his ex-wife Catherine Deneuve. No, he ever learned a word of French throughout their marriage. This is typical of the man: a rough diamond, even in his seventies. Directed by Jerome de Missolz for White Rabbit/ZDF.

We’ll take Manhattan

This drama tells the story of Winter 1962, and cockney photographer David Bailey and unknown model Jean Shrimpton are sent to New York for a prestigious Vogue photo shoot. A wild week, their love affair, terrible fights with their fashion editor – and how two young people with no such intention happened to change the world of fashion forever. A brilliant film featuring Karen Gillan as Shrimpton and Aneurin Barnard as the young Bailey, directed by John McKay (Reichenbach Falls, Life on Mars)

Massive thanks to David Bailey, Vogue, Conde Nast, BBC, The Independent and Wikipedia

All images © David Bailey