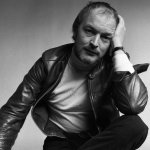

The name Brian Duffy is not as well known as it should be – more synonymous as the photographer that burned almost his entire collection of transparencies and negatives in 1979. The son of an IRA man who did time for murder, Duffy grew up running wild on the bombsites of 1940s London, until he was enrolled in an experimental school that believed in rescuing delinquents through art. It worked, though he remained notoriously irascible: once, when a model smoked cigarettes carelessly in Duffy’s studio, he tipped the ashtray into her handbag. “Difficult” is how Bailey describes his great pal: “Duffy and aggravation go together like gin and tonic.”

Duffy never intended becoming a photographer. Studying dress design at Saint Martins College of Art, he pursued brief stints in fashion design and illustration before deciding to try photography, starting at Carlton Studios in 1955, working with photographers such as David Hurne, Ivor Sharpe and the legendary Ken Russell, then left to become fourth assistant to Adrian Flowers. Duffy picked up his first commission from the Sunday Times in 1957, the year that he started at Vogue. Quickly becoming a Vogue favourite, Duffy’s avant-garde style was instrumental in pushing the formerly society-led magazine to remain relevant as the teenage revolution ensued. Duffy was one of the ‘terrible trio’ of photographers in the Sixties whom society photographer Norman Parkinson called the ‘Black Trinity’, and who helped to capture (pun intended) the shape and vibrancy of the London fashion scene, along with fellow Eastenders David Bailey and Terence Donovan.

They were great mates but also great competitors working at the cutting edge of the ‘Swinging Sixties’, redefining not only photography but also the image of a photographer. They pushed each other to new heights creatively and often technically, spending many nights talking, living and breathing photography. Their inventive compositions were looser than the stiff, stuffier studio portraits of the 50s. Duffy later explained: “Before 1960, a fashion photographer was tall, thin and camp. But we three are different: short, fat and heterosexual. We were fairly chippy and if you wanted it you could have it. We would not be told what to do.”

Brian Duffy quickly became one of the leading fashion, glamour and celebrity photographers of the time, documenting society figures like the Kray twins as well as celebrities Michael Caine, Bridget Bardot, Sidney Poitier and Charlton Heston.

The iconic image of David Bowie (Aladdin Sane 1973) is stunning not just for its simplicity but also its starkness – the naked torso of Bowie with his eyes closed contrasts with the flame red mullet and red lightning streak (created by Duffy himself using lipstick). Philip Castle, famous for his artwork for Stanley Kubricks film, A Clockwork Orange, was enlisted to work on the portrait, create the silver air brushed Aladdin for the gatefold, and place a tear-drop in the collar bone.

Duffy’s commercial work is often overlooked but is, in my opinion anyway, as important – work for Benson & Hedges and Smirnoff is as iconic as his fashion work, and started the surreal/abstract ball rolling for the B&H ads, working with Collet Dickison Pierce (CDP) especially, creating a whole genre that would last for many years and inspire people like Graham Ford, Stak, David Puttnam and Ridley Scott.

The Benson & Hedges ads were to be created in Duffy’s studio in London’s Swiss Cottage. The first one of the series showed a cigarette packet outside a mouse hole in a skirting board, in the place where a mouse trap would normally appear. Duffy shot the scene using four or five different lighting set-ups before he was happy with the image. It established the style of the campaign and he moved on to the next image, ‘Birdcage’.

Duffy’s son Chris, who was an assistant on all the B&H shoots, remembers that the unreal, slightly distorted sense of perspective in these images was partly created by his father’s choice of kit. ‘Duffy had taken a Cambo 5×4 and had custom-built a fitting on the back that took Mamiya 6×9 press rollbacks,’ he says. ‘It was his favourite camera and he used about 12 different lenses on it, all taken from other specialist cameras.’

The ‘Birdcage’ image showed what appeared to be a green-painted room bathed in late-afternoon sunlight. To the right of the image was a cage with a B&H packet on the perch, but the shadow on the wall behind showed a bird in the cage.

‘It was a very simple set,’ Chris continues. ‘We lit it with an old Rank projector light and through it we projected an image of a bird that we had reversed out on a negative.’

Two more images in the series followed: one showed a matchbox with a bird’s egg inside, out of which had ‘hatched’ a B&H packet; another featured a gold ring with a cigarette packet set into it.

Commenting on these images in a rare interview in 2009, Duffy said: ‘I changed the colour and scale of everything, which looks pretty weird today. I played with optical illusions, since I know enough about what lenses can do and plate cameras and changing perspectives… They’re real photographs and it’s quite complex to do things like that, which look like trick photography. They’re not phoned in from the coast, it’s all done in the camera.’

The campaign was an instant success and the images were regularly shown in newspaper and magazine spreads and on advertising hoardings. These images became regarded as some of the most original in the history of advertising and garnered a number of industry awards.

The BBC documentary ‘The Man who shot the Sixties‘ is a sensitive feature on the photographer and his work, and revisits the site where, fed up, he burned his negatives in 1979. At the time, he said that he had said all he could say through the medium of photography. He recognised later that it was a breakdown but did not have regrets – “life is life and things happen”. The fire was stopped by a Camden Council official after complaints.

“The thing with negatives is they don’t burn as fast as you think they will. I’d thrown them into this fire bin and I just had to stoke them and I was pouring white spirit in to try and keep it going. It was, to be honest, making pretty stinking black smoke.”

And that was it. Brian Duffy didn’t pick up a camera for about 30 years, preferring to live in relative obscurity – even his children were unaware of his work and its importance until, in 2007, Duffy’s wife suggested he might like to do something with all the shoeboxes full of un-burned negatives cluttering up their home and his son Chris began going through them. “He started looking through them and said, ‘Wow, there are some really interesting things here, didn’t realise you did this or that”. Duffy said it had not really occurred to him that people would be interested. “What’s happened over the last 20 years is that photography, which was a trade, has now become art.” He said he had always considered himself a craftsman, albeit a very good one.

Sadly, Brian Duffy died on 31st May last year, having lost his battle to pulmonary fibrosis.

David Bailey told The Sunday Telegraph “I will deeply miss arguing with him. If you said ‘Good morning’ to Duffy, he’d question it, that was his charm but I could do that Cockney thing with him of defusing it with humour. Cantankerous was a word made for Duffy, it was just his character. You always knew it was never going to be dull with him, because he was always going to pick an argument somewhere down the line.”

The Man Who Shot the Sixties (full length film) by BBC, directed by Linda Brusasco.

A new exhibition of his work features more than 160 images which have been painstakingly rediscovered by Chris Duffy, and feature top icons from the 1960s and 70s. Michael Caine, Brigitte Bardot, John Lennon, David Bowie, Jean Shrimpton and Joanna Lumley all feature in the show.

Duffy runs 8th July – 28th August 2011 at Idea Generation Gallery, www.ideageneration.co.uk.

The first ever book devoted to the work of Brian Duffy will be published by ACC Editions in July. Duffy: 9781851496570, £45. To order a copy call 01394 389977 or go online at www.accpublishinggroup.com.

with thanks to Amateur Photographer, Chris Duffy, BBC, Wikipedia & Idea Generation Gallery and Creative Review

All images © Chris Duffy & Brian Duffy